Writing High School Lesson Plans

Far too many first-year teachers enter the classroom without the essential knowledge of how to write a real lesson plan. Education classes often gloss over the importance of the planning stage of a teacher’s career. This guide is intended to help bridge that gap for the new teacher, but even experienced teachers can often benefit from a new perspective. Lesson planning is arguably the most important part of a teacher’s job. An engaged, interested student will retain more of the lesson than a bored, disinterested student, and the engaged student is less likely to need discipline corrections. If you want to reach your students, your first step must be done before the lesson ever starts. Students can tell when a teacher is not prepared, and there will always be individuals in the classroom that want to take advantage of the situation to try to bring chaos into the classroom. You can eliminate many discipline issues when the lesson flows from one step to another with smooth transitions that do not give the students time to get distracted. The easiest way to achieve these transitions is to have a plan that you can from beginning to end.

Before you start any lesson plan, it is important to know what your employer expects. Lesson planning is often discussed in

staff meetings before a school year starts, but too often it is only when lesson plans are due to the principal with no

discussion of format. Your principal is always the best source of information but talking to your department head is just

as important.

Using a template. Some schools or districts require that you use their template. If yours does not, simply following the

guidelines of this document will give you a legitimate format for your lesson plans. You can also find templates by searching

on the internet, but beware, your template should give you a detailed guide to planning everything that you will need to be

successful in the classroom and include anything that your district requires.

Standards that the lesson covers

Objectives

A lesson starter

Detailed activities

Assessments

Differentiation strategies

You should have a place to include each of these items in your written plan.

Fifty-one states in the U.S. have adopted the Common Core State Standards of education (Common Core). These standards outline the subject matter that the state expects teachers to cover in their lessons throughout the year. While most of the states have adopted the Common Core State Standards, there are still a few, including Texas, that use their own standards. Texas’ standards are named Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS. The Texas Education Agency gives these standards in a codified organization that allows each subject, standard and substandard to be referred to by its code. New teachers can easily feel intimidated when they read standards the first time. It is important that you seek out and use every resource that you can find.

- Schools or districts often create curriculum maps that will break down the standards into a timeline, using plain language to map out what should be taught on a weekly or monthly basis and attaching the standards code to each block of time.

- The most valuable potential source of help should be fellow teachers who teach the same class. Ask these teachers if they plan on meeting weekly to plan as a group.

- Ask for help. Planning lesson with fellow subject matter teachers or your department head can help a new teacher avoid many of the pitfalls of first year teaching.

Simply put, your lesson objectives are the goals of your lesson. Your objectives should always be tied directly to the standards you are covering with that lesson. The major difference between standards and objectives, and the reason they are discussed separately, is in the presentation of the objective. While your standards are codified and brief, your objective should always be worded in plain language meant to be easily understood by your students.

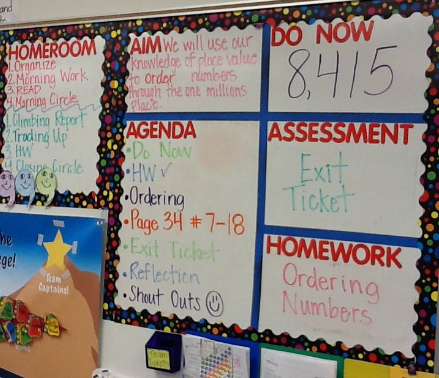

- Write your objective as a “we will” statement, as seen in illustration 1, or as a question. Teachers who write it as a question often ask their students to answer the question at some point during the lesson, either directly or as a problem they must work through.

- Write your objective so your students can understand it without your help. They should not have to guess what they are supposed to learn each day, but it should be presented to them from the beginning of each class.

- Post your objective in an easily seen place in your classroom so that your students can see it when they enter. Illustration 1 gives an example of a board configuration for students to read. This teacher calls the objective the “aim.”

Not all schools require that the teacher start a lesson with some form of starter activity, but a savvy teacher will have something in place for students to do as they enter the classroom. Potential problems in your classroom can be greatly reduced if a beginning of class routine has been put in place.

- Avoid situations where students come in, sit down and just wait on you to enter the classroom, take attendance, and get organized before anything is expected from them. You will be facing a class that is loud and possibly chaotic before you ever have a chance to start.

- From the beginning of the year, set the expectation that they enter, sit down, and begin working on a lesson starter. You will be giving yourself a time to take attendance and gather your thoughts while they begin the lesson on their own.

- Each day, post a lesson starter on your board that gets the student actively thinking about an issue or goal from the content they have or will learn. It should not take a student more than five minutes to complete.

Illustration 1 has a lesson starter labelled as the “do now” because the expectation is that students will enter the classroom and immediately start on the problem. Some schools call the lesson starter a “bell ringer” to indicate it should be started as the bell rings to start class. In the example, the teacher only wrote a number on the board, but the students will know exactly what to do with that number as they enter the classroom. It is a perfect example of the simplicity you are looking for when you create a lesson starter.

Some examples of lesson starters:

- Define a keyword from their textbook

- Ask a question from yesterday if you plan to continue that lesson

- Ask a question that ties today’s lesson to a previous lesson

- Reflect on a current issue tied to today’s lesson

- Ask for an opinion on a matter that is tied to today’s lesson

- Ask a “suppose” question that is tied to today’s lesson

Successful activities must build on the knowledge and skills necessary for the students to meet the standards set forth by your state. Activity planning should include your own actions in the lesson as well as what the students will be doing in each step.

- At each step of your planning, you should be thinking about your students and how they learn. Every student is different, so a wide range of methods should be used to engage students.

-

Plan out how you will introduce the day's lesson to the students. This often means a lecture session of some sort, but

that does not mean you need to be planted at the front of the class and talking while students sit and do nothing but listen.

At minimum, students should be taking notes. Visual aids such as a PowerPoint presentation could accompany your lecture

but be careful to use the visual aids as supplements that do not overwhelm what you are saying.

Note: Notice how speaking covers auditory learners' needs, visual aids help visual learners, and taking notes can help kinesthetic learners, especially if you pace the lesson to allow all students to illustrate their notes with doodles, highlighting, or marking. -

No matter how interesting your lecture is, students will quickly become restless if that is all you do during a class period.

It is important to plan small breaks in any lesson where restlessness and inattention could be a problem. These are commonly

called "brain breaks," and including them in your plan every 10 to 15 minutes allows students to move, engage the lesson in

diverse ways, and break up the monotony of a lesson.

- Stop and have them compare their notes with a nearby classmate.

- Play a short, 5-minute game that reinforces the lesson, or anything that gives them a break from listening.

- Have them write a reflection or summary of what has been covered so far.

- Give them questions to discuss with a nearby partner and then ask pairs to share the answers they produced.

- Plan for student practice. What will the students do to apply what they have learned? It is important that students practice what they learn whether it is in individual assignments or group work.

- Estimate the time that each step of your lesson will take. Planning what you think will be too much is better than realizing you have finished with your planned lesson, and you still have 15 minutes of dead time left in the class period.

- Give yourself a timeline for giving feedback. Feedback is important to any lesson cycle. If the student does not know how they did or what they did wrong, they cannot improve.

How you plan on assessing your student’s understanding of the content can be included in the activities section of your lesson plan, but it has been separated here to emphasize the importance. Assessment should be a constant process for a teacher.

- Use keywords to note how you will assess student understanding. Keywords such as “questioning” or “quiz” in your lesson plans are enough to give yourself a reminder of what you intend on the day of the lesson.

- Informal methods will make up most of your assessments. This can be as simple as noting who is not paying attention and redirecting them back to the lesson, asking questions throughout the lesson or even walking around and looking at the work each student is doing at their desk.

- Formal methods include quizzes and exams that you will grade and return as method of feedback to the student.

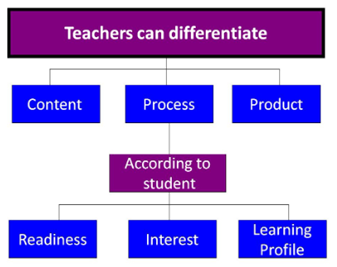

There are a multitude of ways to differentiate a lesson, in fact there are so many different approaches to differentiation that it can be overwhelming for a teacher to consider. Let us look at one definition of the term.

“Differentiation means tailoring instruction to meet individual needs. Whether teachers differentiate content, process, products, or the learning environment, the use of ongoing assessment and flexible grouping makes this a successful approach to instruction.” (Tomlinson)

It is impossible for a teacher to write lesson plans that touches each individual every single time, so first recognize that you are not including the differentiation plan for every student. However, on that note a teacher must recognize that many special education students will have Individual Education Plans, or IEPs, that, by law, must be followed in your classroom. Rather than write individual lesson plans for every IEP, it is expected that you will keep each student’s paperwork on file in your classroom and refer to them as needed.

Your district might have specific expectations of how you include differentiation in your lesson plans. If it does not, then in the simplest form of planning, you will need to address three areas.

- Students who have shown low levels of understanding in your assessments. These students might need supplementary materials, or they might need the material presented again in a different way. Whatever the case, they need your help to be brought up to speed on the lesson content.

- Students who have shown they understand the content enough to meet state standards. These students need challenging lessons that will continue to grow their knowledge and understanding.

- Students who have shown mastery of the content being presented. These are the students who are ahead of the rest of the class. This group needs enrichment lessons to avoid becoming bored and complacent.

States do have standards for using technology in the classroom. These standards are in addition to the subject area standards and apply to every classroom, regardless of the topic. These standards focus on student use of technology. A frequent hurdle for teacher to overcome is lack of devices in the school, so make sure you have secured the use of them before you plan a lesson that relies on students using technology. On the other hand, if you are a one-to-one school, meaning every student has a school issued technology device, you might be required to include technology standards in your daily lesson plans.

Plan to take advantage of technology when you can, even if it means reserving technology months in advance. Student creativity can be unleashed without the need for extra supplies, but be aware that such a lesson might need extra time for you to instruct students on how to use the device to meet your expectations.

It is important that you reflect on each day’s lesson at the end of the day. There will be some days that you walk away knowing you will never use that lesson plan again. Other days you will mentally put a checkmark on a lesson and deem it a complete success that you look forward to using next year. Most lesson will fall somewhere in between those extremes. Reflect on what worked and what could be improved. Get in the habit of making notes on each lesson plan to keep for the next year and your future lesson planning will be progressively easier.

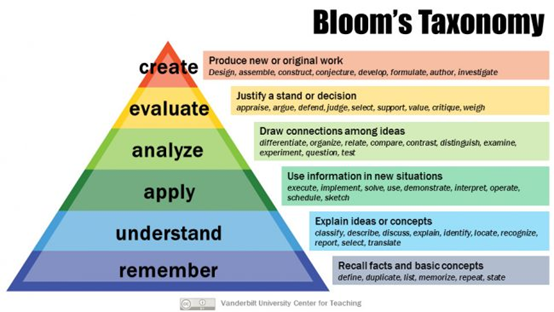

Armstrong, Patricia. “Bloom’s Taxonomy.” Vanderbilt University: Center for Teaching. 2022.

cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Common Core: State Standards Initiative. 2022. www.corestandards.org/standards-in-your-state/.Pinterest: KIPP Bloom Whiteboard. n.d. www.pinterest.com/pin/clear-and-effective-board-configuration--469922542337956437/.

Tomlinson, Carol Ann. Reading Rockets: What Is Differentiated Instruction? n.d.

www.readingrockets.org/article/what-differentiated-instruction.

Tomlinson, Carol Ann and M. B. Imbeau. Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom. Alexandria, VA:

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2010